Primary spiritual practice is whatever one does just to be doing it -- for its own sake -- without thinking about achieving anything or whether it's being done "right." One's primary spiritual practice can be almost any activity, and primary practices vary widely from person to person. Secondary spiritual practices support, amplify, expand, and deepen the primary practice. Secondary, supportive spiritual practices are much fewer and less individual: there are five of them, and all five are for everyone.

Physical Health, Cognitive-Intellectual Health,

Emotional-Social Health, and . . .

Spiritual Health?

About a month ago, I signed up at a web site for brain exercises. It's called lumosity dot com. (

Click here.) I log on in the morning and I play a series of brain puzzle games that are supposed to keep my neurons strong. Some of the games exercise memory, others mental flexibility, or problem solving, or speed, or, attention. I don't know if it's really going to improve or help in maintaining cognitive function. But it might. It's only about 15 minutes a day, and it's kinda fun, so it seems worth a shot. And I got

LoraKim signed up, too, so we can compare our scores.

I also do some physical exercises -- stretches, sit-ups, go for walks, ride my bike. Brain exercises for cognitive fitness (maybe), and physical exercises for physical fitness (definitely).

Then there's emotional fitness -- also called “emotional intelligence”: the ability to detect and identify emotions in self and others, harness emotions to facilitate the task at hand, and understand the language of emotion, including ability to recognize slight differences between similar emotions. Some of us are really good at that -- others, not so much.

|

A pyramid showing Physical, Intelligence,

Emotional-social, and Spiritual Quotients |

Closely related to “emotional intelligence” or fitness is social intelligence -- because really resonating with someone, clicking with them, is a matter of knowing your feelings, recognizing theirs, and being able to synchronize with the emotion.

There's physical fitness, cognitive fitness, emotional fitness, and social fitness. So: Is there such a thing as Spiritual Fitness – spiritual health, spiritual intelligence? I have two things to say about that.

Number one, yes, there is a way to measure spirituality, and there are exercises to boost your spiritual fitness.

Number two, no, spirituality is not at all one more kind of fitness, and the very idea of spiritual fitness completely misses the point.

First, let’s look at number one: there is spiritual fitness; it can be measured; and training can improve it.

Defining Spiritual Fitness

According to psychologist Robert Cloninger's work in this area, "spirituality" cashes out as self-transcendence -- an orientation toward the elevated, whether that is experienced as compassion, ethics, art, or whether it is experienced as a divine presence. By orienting toward the elevated, we transcend the ego defense mechanisms by which most of us spend our lives governed.

Self-transcendence is the sum of three subscales:

- self-forgetfulness;

- transpersonal identification; and

- acceptance.

|

| C. Robert Cloninger (b. 1944) |

Self-forgetfulness is the proclivity for becoming so immersed in an activity that the boundary between self and other seems to fall away.

Transpersonal identification is recognizing myself in all things, and all things in myself. As the poet Kabir said, "Everyone knows the drop merges into the ocean, but do you know that the ocean merges into the drop?"

Acceptance is the ability to accept and affirm reality just as it is, even the hard parts, even the painful and tragic parts.

Cloninger has devised a questionnaire to measure self-forgetfulness, transpersonal identification, and acceptance. Add those three scores together to get the self-transcendence score. Voilá, we have measured "spiritual fitness."

(See Wikipedia's entries on Robert Cloninger,

here,

and on Cloninger's Temperament and Character Inventory [TCI]

here.

You can take the TCI on-line [payment required]

here.)

Many different phrases have been used to express the spiritual capacity – the capacity to:

- see beyond walls,

- commune with divine mystery,

- experience an internal caress,

- hear our deeper consciousness,

- experience epiphanies,

- become awake,

- usher ourselves into right relationship with life,

- open our heart to life's blessed mysteries,

- foster a greater love of self and greater caring for neighbor and earth.

According to Cloninger, what we’re really talking about with these metaphorical and poetic phrases, is self-forgetfulness, transpersonal identification, and acceptance.

Now let me say where all of this seems to me to miss the point, to go astray.

The Paradox of "Spiritual Fitness": Judging Ourselves for Being Too Judgmental

Our culture has a mania for self-improvement -- whether it's in the physical area, the cognitive, the emotional, or the social. Get more physically fit: Exercise, diet. Be smarter, train your brain for greater memory, speed, attention, flexibility, and problem-solving. Hone your emotional skills, sharpen your social skills. Here's what you need to do to win friends, influence people, get the promotion, achieve success, make your marriage work and/or get that cute man or woman to notice you, find fulfillment, be energized, get the respect you deserve, prevent wax build-up, and fight tooth decay.

These are the themes that fill the shelves of the self-help section. There's even a self-help book on how to write a bestselling self-help book -- because, you don't really have it all together unless you have written a book to explain it to the rest of us.

Over and over we are told: whoever you are, you're not good enough. Wherever you are on life's journey, you really ought to be further along by now. Whatever your grief or burden or wounding, get over it. Get fixed.

Oddly, at the same very same cultural historical juncture at which we judge ourselves unworthy at every turn, we are also more prone to judge ourselves greater than we are.

Ninety-three percent of US drivers identify themselves as above-average drivers. Ninety-four percent of college professors believe they have above-average teaching skills.

"In the 1950s, 12 percent of high school seniors said they were a 'very important person.' By the '90s, 80 percent said they believed that they were" (David Brooks, citing Jean M. Twenge,

New York Times, 2011 Mar 11.

Click here.) And it's no wonder: our young people, more than any previous generation, have been "bathed in messages telling them how special they are."

We think we're better than most others -- better than average -- and at the same time, think we're not good enough. We yearn to be further and further above average -- which means more and more distance (perceived distance anyway) between ourselves and other people. There is actually no contradiction: we simply judge ourselves inadequate, and we judge other people – average people – even worse. Our more agrarian great-grandparents were certainly capable of passing judgment, but I don’t think it consumed their lives as often as our judgmentalism consumes ours.

There is a place for judgment, evaluation, good-bad, better-worse -- and there always will be. Judging Mind has important work to do. The problem is that it works overtime. Judging Mind seems to want to take over when what we would like it to take is a break. Spirituality is about seeing the appropriate, limited role for judgment -- while also holding in our awareness the wider context within which judgment has its little corner. That wider context transcends our petty assessments of better and worse.

Your spirit is the part of you that understands that you are good enough – that you are, in fact, perfect – and any approach that says spirituality is one more area where you’ve got to get better undermines the very spirituality it purports to encourage.

We might look back on moments of self-forgetfulness and realize we were performing very well. At the time, in the moment, we weren't thinking about our performance as good or bad. We had lost the sense of being a separate self to judge better or worse and were just flowing, like a current in a river that has no concept of itself as separate from the rest of the river or from the rest of the earth's waterways. As soon as the thought enters your head, "hey, I'm playing superb tennis today," or "I'm painting a real masterpiece here," the spell is broken.

Transpersonal identification is recognition that we are the other -- and there's no place there for judging ourselves better than others, better than average.

Spirituality involves acceptance, the affirmation and embrace of reality exactly as it is, not judging ourselves or others as needing to be better.

That's why I say the very idea of spiritual fitness misses the point. We aren't going to learn to be nonjudgmental by judging ourselves for being too judgmental. The spiritual path is not about fixing something that's broken about you. It's about the abiding truth that you aren't broke, and don't need fixing. You really are perfect exactly the way you are, and couldn't possibly be any better.

Here I am with my judging mind, asking: How can I turn off this judging mind? I can't make it happen. However I might characterize it -- being awake, more epiphanies, inner peace -- I can't make that happen. As soon as I think there is such a thing as a separate me, and soon as I judge it as not spiritually healthy enough, I have erected an impassable barrier. My very effort to take it down is what makes it stronger. I'm telling myself: "Try harder . . . not to try so hard."

It's Not Up to You. Except the Part That Is.

I love Unitarian Universalism and Unitarian Universalists, and have committed my life to our faith. I love us, and I do want us to be all we can be. I know that one criticism of UUs goes like this:

Unitarian Universalists are dabblers and dilettantes -- highly knowledgeable and intellectually curious, but spiritually rather frivolous. They seem to think they understand the taste of the food just from reading the cookbook. They seem to believe they'll get strong muscles by attending a lecture on weightlifting. UUs, by and large, are not serious about their spiritual development.

Some of that criticism is unfair. The criticism results from misunderstanding the way that valuing diversity works. Our commitment to diversity and our appreciation of the rich rewards of a diverse community do not mean that each individual UU is required to be uncommitted to anything other than diversity itself. It does mean that a UU’s spiritual practices include cultivation of, and delight in, affectionate relationships with others with different practices, perspectives, and understandings. "Include" does not mean "are limited to." Unfortunately, too many UUs themselves seem to have accepted the misunderstanding and approach religious life as if diverse community were sufficient. Thus, the criticism has some partial truth to it. So here's what I want us to know:

Number one, know that it's not up to you. You can't make it happen. You can't fix yourself. Indeed, you're not broken, and can't possibly be any better. That's the first lesson, and that's also the last lesson, because only in rare moments do most of us manage to truly believe that.

Number two, in order to really "get" number one, there are some things that

are up to you. There are spiritual practices. Why would I do practices since I'm already perfect? I might start doing them because I don't

feel perfect. As contradictory as it is to judge myself for being too self-judgmental, that's exactly what I do.

Embrace Your Demons

I began spiritual practice because I was beset by my various demons. I had been fighting them for years, and was not winning. Apparent victories were temporary, fleeting. The fighting just gave the demons a good work-out and made them stronger.

Spiritual practices are ways to stop fighting. If I embrace my demons instead of fighting them, then they aren’t such a problem for me, or for the others in my life.

I can't make this happen, but what I can do is practice stepping back to see what my fears, my insecurities, my judgments of inadequacy might do on their own if all I do is steadily acknowledge them. They start to fade away on their own. Of course, they don't entirely leave. They come back for visits. They send me a card on my birthday. (They're so thoughtful, these demons!)

I sit and try to notice the thoughts and feelings that arise: "There's judgment.

Again. There's the judgment that I shouldn't have judgment.

Again." Don't resist, just notice.

Will that do anything?

Ah, this is why we call it faith. I take the leap of faith of opening myself to all those demons, opening my heart to the unknown, trusting that they will sort themselves out as they need to. I can't make myself be at peace. What I can do is pay loving attention to the things that give me turmoil. What I discover is that the waves gradually get smaller, and further apart.

Nothing to Attain: The Primary Spiritual Practice

We might start a spiritual practice wanting our spiritual muscles strong, toned, trim, and limber. If we do keep at it, we might gradually come to see that there's nothing to attain – except the knowledge that there’s nothing to attain.

A visitor to a Zen center heard the master give a dharma talk saying Zen is about being ordinary. Afterwards the visitor asked the master, “Ordinary? So, then, what is the difference between you and me?”

The master said, “There is no difference – only, I know that.”

We do the practice not to attain something. We do the practice just to do the practice. Dishwashing becomes spiritual practice when you aren't washing the dishes to get them clean; you are washing the dishes to wash the dishes.

There are many, many forms of spiritual practice. There's the traditional idea of spiritual practices: Bible study, prayer. Unitarian Universalists have many other spiritual practices: yoga, martial arts, social action, vegetarianism, living simply, cooking, eating, not eating (fasting), quilting, art. There's gardening, hiking in the woods, walking along the beach, playing a musical instrument or singing or listening attentively to music. Any number of things can be spiritual practices if they are approached with a deliberate intention to get out of our judging mind for a while, and just accept, affirm, and appreciate -- allow self-forgetfulness and transpersonal identification to come over us if they will.

Think about something you do just to be doing it, something you do without thinking about achieving anything, without thinking about whether you're doing it the way you supposedly should be doing it. There's your spiritual practice. It is the place in your life where you are liberated from your own judgmentalism, freed from the pursuit of goals and purposes, and allowed to bask in just being.

It feels nice, doesn't it?

And then there's all the rest of life.

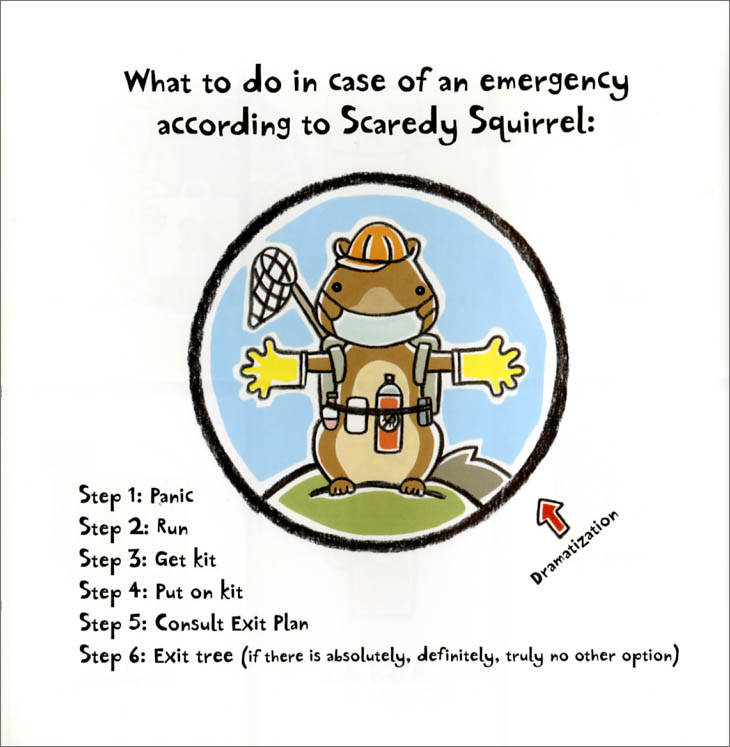

Five Secondary Spiritual Practices for Everyone

Maybe you would like to infuse all of your life with a bit more of that spirit. As I say, we can't make that happen. All we can do is invite it to happen. There are five particular practices to invite our spirituality to infuse more of our lives. Whatever your main spiritual practice is, these five supplemental practices will provide a foundation for it. Our main spiritual practices are highly varied -- these five support practices I recommend for every single one of us as a way to strengthen and extend your spiritual practice and your "spiritual fitness."

- Journaling

- Reading

- Silence

- Group

- Mindfulness

First, journaling. Fifteen minutes a day. There are many different approaches to journaling. Here's a simple starter plan. Six days a week, “just keep the pen moving.” Write whatever comes to mind for 15 minutes. Then, on the seventh day, list in your journal five things that week that you are grateful for.

Noticing is the key to spiritual acceptance, and writing down whatever comes to your mind is helpful for noticing what is alive in you. (My further reflections on journaling:

click here.)

Second: "Scripture" study -- with a very wide understanding of "scripture." Again, 15 minutes a day. Select a text of “wisdom literature.” The scriptures of any of the world’s religions are worthy texts for spiritual study. The

Dao De Jing, the

Bhagavad Gita, and the Hebrew Bible's book of Psalms are wonderful places to start. Also worthy would be books like Thomas Moore’s

Care of the Soul, or reflections like Thomas Merton's, or poems of Rumi, Hafiz, or Kabir, or writings by St. Francis, Teresa of Avila, Julian of Norwich, Rabindranath Tagore, Gandhi, Pema Chodron, Thich Nhat Hanh. Any of these will do nicely. Choose works that resonate with you, and commit to study them a few minutes every day.

What this does is enlist your cognitive capacity to assist your spiritual. We live through our days full of ideas and concepts -- and most of them are connected to some form of judgment, some form of not wanting things to be as they are. Wisdom literature helps give us some concepts that can nudge some of those other concepts a little bit into the background more often.

Third, silence. Another 15 minutes a day. I know, this is adding up -- and, gosh, aren't we all too busy anyway? Who has time for stuff that has no purpose? I can't answer that. When the quest for peace is urgent, the time is not the issue.

Find a posture that will allow you to remain still. Bring attention to your breath. When (not if) your thoughts wander, simply notice where they wandered to and return to your breath. This simple practice begins to cultivate awareness of your own thoughts – and helps you get to know the true person you are that is so much more than just your thoughts.

Fourth, group practice. Monthly is good. Bi-weekly is better. Go weekly, if you can manage it. A group that shares in your primary spiritual practice, whatever it may be, is a great boon for deepening in that practice. If walking on the beach is where you have had the best luck experiencing serenity, get together a beach-walking group -- in addition to having some time to walk alone. If it's cooking, get in a cooking club -- only, be sure it's a cooking club that intentionally approaches cooking in a spiritual way.

Just as study helped enlist your cognitive to assist your spiritual, the group experience enlists your social brain on behalf of the spiritual. And that helps invite the spiritual to infuse more of your life. It's so important to know that you're not going it alone!

Fifth, resolve for mindfulness. Continuously. Develop the habit of bringing yourself back to the present moment whenever you find that you’re somewhere else. These are not the practices that will make you perfect. You’re already perfect. They might not change anything at all -- and that's going to be discouraging for that judging mind that wants results.

My intention is for my Judging Mind to just do its job and stop being such a totalitarian tyrant. I can't make that happen, I can only keep inviting it, over and over, day after day, year after year.

My faith is that an awakened life is possible. I am called toward that possibility -- not because it's better -- that would be a judgment -- but just because it is who I am.

Nurturing my spirit. Helping heal our world. For real?

For real.

* * *

For a somewhat revised and expanded version, posted in seven parts, begin here.